Discerning Meaning: Examining the Relationship between Religious/Spiritual Meaning and Stress

Abstract

This study examined the relationships between gender and stress on religious/spiritual (R/S) meaning struggles through a mediation analysis. Participants (N=736) completed the Religious and Spiritual Struggles (RSS) scale to assess for meaning of life struggles as well as the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress scale (DASS) to assess for stress levels in the past week. A simple mediation model demonstrated a partially standardized effect of the indirect path of -.113 (-.181, -.046), a small effect. The mediator stress increased the direct effect of gender on meaning of life struggles to a statistically significant total effect of -.213 (p = .004), a between small and medium effect. This may suggest males are more likely to endure higher levels of stress which may in turn increase the likelihood of encountering meaning of life struggles than females.

Literature Review

The link between religion/spirituality (R/S) and mental health has been extensively demonstrated (Abu-Raiya et al., 2015; Appel et al., 2019; Garssen et al., 2021; Wilt et al., 2022; Zazycka & Zietek, 2018). R/S struggles can be defined by moments when life stressors lead to questioning fundamental assumptions that might have previously held a position of comfort for the person (Abu-Raiya et al., 2015). R/S struggles related to meaning – as measured by the Religious and Spiritual Struggles Scale (RSSS) – may include questioning whether there is a purpose to life and meaning in it, or if life matters, intra- and interpersonally (Exline et al., 2014). Stress – as measured by the Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scale (DASS) – has been found to represent a different set of symptoms from depression and anxiety, which sometimes overlaps with anxiety, but is separately defined as a state of being in which the person feels arousal and tension with a tendency of being easily upset or frustrated (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995).

Both positive (Appel et al., 2019) and negative (Abu-Raiya et al., 2015) effects of R/S on mental health have been explored. Emphasis on the relationship between R/S struggles and depression, anxiety, and stress (Wilt et al., 2022) have been especially helpful in assessing the degree to which they could affect each other. Positive correlations between meaning violations – which consisted of the interference of life goals and beliefs – and post-traumatic stress (PTS) have been observed (Appel et al., 2019). Women who have lost a child before birth have also shown a diminished sense of purpose and meaning in life (Guzewicz et al., 2014). This and other studies with college students (Shin & Steger, 2016), new mothers during a crisis (Chasson et al., 2021), and nurses (Nowicki et al., 2020) all emphasize the importance of social support during a crisis, especially when considering meaning in life. Due to the importance of meaning in life during periods of stress, more in depth information is needed to bring greater understanding for those struggling with meaning of life questions when enduring deeply stressful situations.

Religious Coping Theory

Religious coping theory (Pargament, 1997) addresses several points of interest to a study of the relationship between stress and R/S meaning struggles. A critique of Pargament’s theory of religious coping reveals strengths in its ability to elaborately examine religious coping through an impartial lens with significant empirical evidence (Xu, 2016). Religious and spiritual resources have been found to be helpful when dealing with major life stressors, however, when life stressors, such as trauma and transitions, affect R/S itself, fundamental assumptions are questioned, which can lead to an R/S struggle (Pargament, 1997).

Abu-Raiya et al.’s (2015) national sample of American adults (N=2,208) found that divine, moral, and ultimate-meaning struggles were predictive of higher levels of depression and anxiety as well as lower levels of happiness for the general population. Experiencing higher levels of depression and anxiety has also been related to greater levels of R/S meaning making struggles (Wilt et al., 2022). Questions remain regarding how stress, a close relative of anxiety, is influenced by R/S meaning struggles during a stressful situation. Does stress lead to seeking meaning of life more, or perhaps does the presence of meaning struggles influence stress – and if so, how?

Religious coping theory aids in understanding how R/S coping can buffer against the effects of stress as long as positive R/S coping strategies are employed (Xu, 2016). This underscores importance of insight into how R/S meaning struggles can lead to negative coping strategies, and ultimately to worsened stress states. Therefore, religious coping theory sets the stage for the exploration of the way R/S meaning struggles are related to stressful situations.

Beneficial Aspects of R/S and Mental Health

Perceiving moments as sacred can lead to positively transformative experiences leading to more adaptive thoughts and behaviors during R/S struggles (Wilt et al., 2018). Greater numbers of sacred moments correlated with more positive R/S struggle related outcomes, including greater spiritual growth and less spiritual decline. Powerful ways to facilitate sacred moments included attempts to communicate with God and beliefs in the efforts being successful (Wilt et al., 2018). They also found a difference among those who placed high significance in their religious beliefs and those with supernatural spiritual beliefs, possibly indicating that some supernatural beliefs are not naturally sacred. Perceiving sacred moments may be beneficial in counseling during R/S struggles (Wilt et al., 2018). Therefore, in difficult times, the belief that sacred moments of communication with God occurred buffered the effects of the stress endured, as does perceiving life as meaningful.

The relationship between PTS symptoms and meaning in life goal violations is weakened by experiencing one’s life as meaningful among college students with academic stressors (Appel et al., 2019). Although findings support that mental health is worsened by R/S struggles, meaning in life had a moderating effect, although only at low and medium levels of R/S struggles (Appel et al., 2019). This may indicate that higher levels of stress may be a threshold, revealing the importance of addressing meaning of life questions earlier rather than later in therapy.

In determining what makes R/S struggles a source of mental health problems or wellbeing, researchers found that through meaning making, religious doubt increased satisfaction with life (Zazycka & Zietek, 2018). Without the mediating effect of meaning making, religious doubt negatively affected satisfaction with life (Zazycka & Zietek, 2018). Perhaps on the one hand meaning struggles may perpetuate a stressful situation as satisfaction with life decreases, while on the other hand, making meaning of stressful experiences can regulate the way religious doubt is handled in order to increase life satisfaction.

As a result of these and other studies, the benefits of R/S on mental health have been empirically demonstrated. In fact, over half of participants in a study of 989 U.S. adults perceive R/S beliefs and practices as supportive to their mental health while 61.7% disagreed their mental health problems were a result of R/S struggles (Oxhandler et al., 2021). Interpersonally, for high levels of R/S struggles, religious discussions at least several times a week, was found to buffer against psychological distress (Upenieks, 2022). In the aftermath of a devastating event, San Roman et al. (2019) found that religious support moderated the relationship between resource losses and R/S struggles. More specifically, those with low religious support who experienced greater resource losses – mainly loss of control, motivation, purpose, humor, optimism, independence, closeness, support, and value – often also experienced greater R/S struggles. Those with high religious support – whether they experienced high or low resource loss – did not differ significantly with levels of R/S struggles. These positive associations between R/S and mental health are contrasted in findings when R/S struggles led to more depression and anxiety, leading to a need for understanding the nuances of the relationship in order to better equip counselors helping those encountering a crossroads of a stressful situation with struggles regarding a purpose or meaning to life.

Harmful Aspects of R/S and Mental Health

Inasmuch as R/S has been described to be beneficial for mental health, the deep nuances and complexities of R/S can lead to a range of perceptions and ultimately considerable effects on a person’s mental health, dependent on the way the person copes when R/S struggles arise (Pargament, 1997). What benefits one can be detrimental for another. R/S struggles are not to be perceived as inherently bad, although they are distressing, because out of an R/S struggle, personal growth can occur (Pargament & Exline, 2022). However, following is research that demonstrates the harm that can be caused by R/S struggles, emphasizing the need for clinicians to better understand how to help someone in the middle of an R/S struggle when facing a highly stressful situation.

R/S struggles have been found to relate positively to depression and anxiety, even when tested over different time frames, such as daily or monthly, specifically with ultimate meaning struggles having demonstrated moderate, positive associations with depressive and generalized anxiety scales (Wilt et al., 2022). Spiritual decline also increased the impact moral and interpersonal struggles have on anxiety (Zazycka & Zietek, 2018). Depression was found to be made worse as a result of financial stressors bringing about R/S struggles (Gutierrez et al., 2017). Therefore, there is evidence for a relationship between R/S struggles and depression and anxiety, however anxiety being closely related to stress (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995) brings about the question of how R/S struggles are related to stressful situations.

In relation to religious doubt, it was found that people who considered dropping out of religion but do not actually leave report a greater increase in mental health problems than those who never seriously considered dropping out, those with no religious affiliation, or those who considered dropping out and did (May, 2018). The doubts unaddressed seemed to have a derogatory effect on mental health. Similarly, when high levels of R/S struggles were discussed infrequently – less than several times a week – psychological distress was higher than for those who discussed them several times a week (Upenieks, 2022). The struggle in a person’s R/S beliefs seem to be exacerbated when issues are perceived but not addressed properly.

Furthermore, a study of 52 veterans presenting for treatment for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) found that compared to community samples, veterans demonstrated greater spiritual and religious faith struggles (Raines et al., 2017). Even more concerning, the greatest correlation in the study was among R/S meaning struggles – measured by the RSSS – and suicide risk, revealing a greater ability of divine struggles and ultimate meaning struggles to predict variation in suicide risk responses.

Therefore, these studies suggest there is a moderating effect of R/S meaning on stress, with the quality of R/S indicating direction of consequent stress reactions. The way meaning of life in relation to R/S can affect the perception of stress is still to be determined.

R/S Struggles and Life Stressors

The theoretical basis for R/S struggles and life stressors in the Religious Coping Theory (Pargament, 1997) adequately sets the stage for the exploration of the way distinctive R/S struggles – especially meaning – lead to different mental health outcomes. R/S struggles, like the struggles encountered during developmental stages, can bring about growth and transformation as the person reorients themselves and commits themselves to finding significance (Pargament & Exline, 2022). This means that whether the R/S struggle has brought about beneficial or harmful effects on mental health during a stressful time, a counselor equipped with understanding of the importance of R/S in life and how R/S struggles impact mental health can provide the hope that is needed to press on in the life of a hurting person.

Of special interest to this study was the finding that ultimate-meaning struggles were predictive of higher levels of depression and anxiety for the general population (Abu-Raiya et al., 2015). Links between stress and anxiety on R/S struggles can also be deduced from the research which found that at low and medium levels of R/S struggle a strong sense of meaning in life can lessen the relationship between posttraumatic stress symptoms and R/S struggles (Appel et al., 2019). Being that there are multiple positive (Appel et al., 2019; Oxhandler et al., 2021) and negative (May, 2018; Raines et al., 2017) aspects of R/S struggles on mental health, it is necessary to better understand the way R/S meaning struggles are related to stressful situations. Additionally, more information is needed on how different age groups and genders perceive R/S meaning struggles at different levels of stress. Although as demonstrated above, the links between R/S struggles and depression, anxiety, and PTS are extensive, there is a need to evaluate the relationship between R/S struggles and stress. For the average person who has a strong R/S belief system and endures R/S meaning struggles in the face of adversity, questions regarding this interaction remain.

Thus, this study’s purpose was to determine whether there was an association between stress levels and R/S meaning struggles, examining differences in gender and age groups using the RSS and DASS scales – and if so, determining what could mediate or moderate the path from stress to meaning struggles or vice versa – with the aim of bringing deeper understanding in counseling those with R/S meaning struggles.

Model Drawings

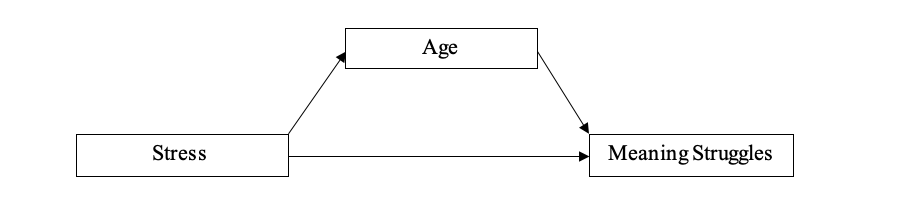

Stress’ close relation to anxiety (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995) lends itself to the examination of how it may be related to meaning struggles due to prior evidence of a relationship between religious/spiritual (R/S) struggles and depression, anxiety, and stress (Wilt et al., 2022). Preliminary data analysis suggests there is a positive correlation between stress and life meaning struggles. The relationship between stress and meaning struggles may have something to do with stress’s relationship with age; therefore, it is hypothesized that age may be the mechanism by which stress exerts in influence on meaning of life struggles.

Figure 1

Simple Mediation Model with Age as Mediator between Stress and Meaning of Life Struggles

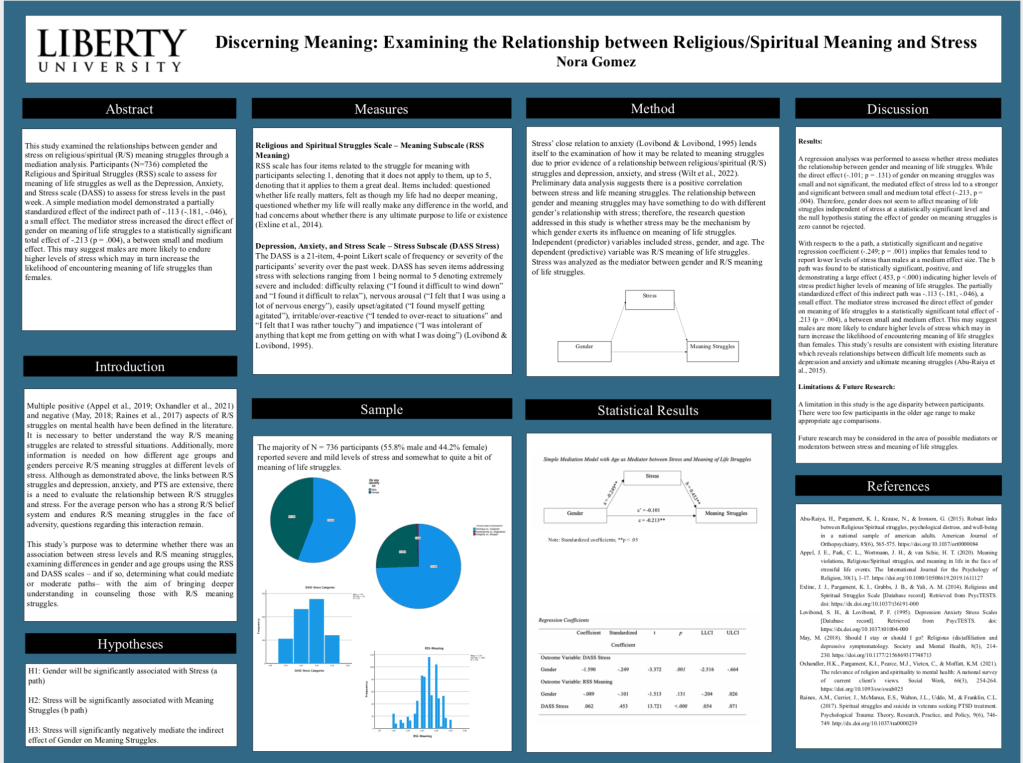

Alternatively, it is possible that the relationship between gender and meaning struggles may have something to do with different gender’s relationship with stress; therefore, stress may be the mechanism by which gender exerts its influence on meaning of life struggles.

Figure 2

Simple Mediation Model with Stress as Mediator between Gender and Meaning of Life Struggles

Hypothesis

H1: Gender will be significantly associated with Stress (a path)

H2: Stress will be significantly associated with Meaning Struggles (b path)

H3: Stress will significantly negatively mediate the indirect effect of Gender on Meaning Struggles.

Measures

Religious and Spiritual Struggles Scale – Meaning Subscale (RSS Meaning)

RSS scale has four items related to the struggle for meaning with participants selecting 1, denoting that it does not apply to them, up to 5, denoting that it applies to them a great deal. Items included: questioned whether life really matters, felt as though my life had no deeper meaning, questioned whether my life will really make any difference in the world, and had concerns about whether there is any ultimate purpose to life or existence (Exline et al., 2014). Participants with higher scores on this subscale were struggling with finding ultimate meaning in their lives.

Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale – Stress Subscale (DASS Stress)

The DASS is a 21-item, 4-point Likert scale of frequency or severity of the participants’ severity over the past week. DASS has seven items addressing stress with selections ranging from 1 being normal to 5 denoting extremely severe and included: difficulty relaxing (“I found it difficult to wind down” and “I found it difficult to relax”), nervous arousal (“I felt that I was using a lot of nervous energy”), easily upset/agitated (“I found myself getting agitated”), irritable/over-reactive (“I tended to over-react to situations” and “I felt that I was rather touchy”) and impatience (“I was intolerant of anything that kept me from getting on with what I was doing”) (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995). Participants with higher scores on this subscale were struggling with physiological and psychological consequences of stress.

Sample

The majority of N = 736 participants (55.8% male and 44.2% female) reported severe and mild levels of stress and somewhat to quite a bit of meaning of life struggles.

Participants were selected for this secondary data analysis from a larger data set collected by Liberty University.

Method

Stress’ close relation to anxiety (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995) lends itself to the examination of how it may be related to meaning of life struggles due to prior evidence of a relationship between religious/spiritual (R/S) struggles and depression, anxiety, and stress (Wilt et al., 2022). The relationship between gender and meaning struggles may have something to do with different gender’s relationship with stress.

Research question

Is stress the mechanism by which gender exerts its influence on meaning of life struggles?

•Independent (predictor) variables included stress, gender, and age.

•Dependent (predictive) variable was R/S meaning of life struggles.

Stress was analyzed as the mediator between gender and R/S meaning of life struggles.

Procedures

Preliminary data screening was conducted to determine if univariate or multivariate outliers were present. One participant’s age was considered a child and therefore removed. Cases selected included only males and females, age greater than 17, DASS-Stress greater than or equal to 2, and RSS-Meaning greater than or equal to 2. Mediation analysis was performed using PROCESS in SPSS.

Results

Analyses were conducted using Hayes Process Macro (Hayes, 2022) on SPSS to assess the degree to which stress mediated the relationship between gender and meaning of life struggles. SPSS output can be found in Appendix 1. Hayes Process produced regression coefficients, p values, and 95% level of confidence for 5000 confidence intervals. Standardized regression coefficients are reported below, with the exception of the indirect path due to gender being a dichotomous variable, which are in partially standardized form.

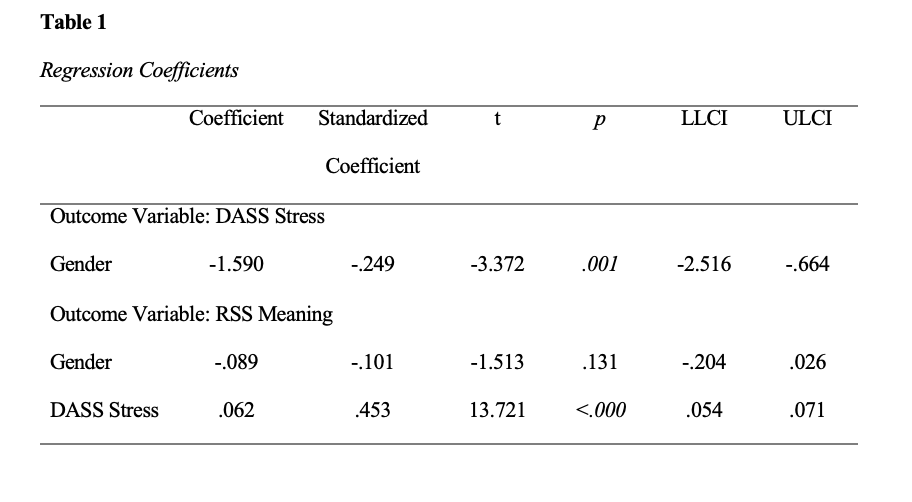

Simple Mediation

A regression analyses was performed to assess whether stress mediates the relationship between gender and meaning of life struggles. While the direct effect (-.101; p = .131) of gender on meaning struggles was small and not significant, the mediated effect of stress led to a stronger and significant between small and medium total effect (-.213, p = .004). Therefore, gender does not seem to affect meaning of life struggles independent of stress at a statistically significant level and the null hypothesis stating the effect of gender on meaning struggles is zero cannot be rejected.

Figure 3

Simple Mediation Model with Age as Mediator between Stress and Meaning of Life Struggles

Note: Standardized coefficients; **p < .05

With respect to the a path, a statistically significant and negative regression coefficient (-.249; p = .001) implies that females tend to report lower levels of stress than males at a medium effect size. The b path was found to be statistically significant, positive, and demonstrating a large effect (.453, p <.000) indicating higher levels of stress predict higher levels of meaning of life struggles. The partially standardized effect of this indirect path was -.113 (-.181, -.046), a small effect. The mediator stress increased the direct effect of gender on meaning of life struggles to a statistically significant total effect of -.213 (p = .004), a between small and medium effect. This may suggest males are more likely to endure higher levels of stress which may in turn increase the likelihood of encountering meaning of life struggles than females. This study’s results are consistent with existing literature which reveals relationships between difficult life moments such as depression and anxiety and ultimate meaning struggles (Abu-Raiya et al., 2015).

Table 1

Regression Coefficients

Discussion

In this study, stress was defined by selection of any level above none of physiological and psychological reactions regarding difficulty relaxing, nervous arousal, agitation, irritability, and impatience on the DASS-Stress scale. Meaning of life struggles were defined as concerns or questions regarding whether life mattered, had a deeper meaning, or ultimate purpose as measured by any score above none on the RSS-Meaning scale. A large, positive effect and statistically significant relationship between stress and meaning of life struggles indicate that those dealing with higher levels of stress are also encountering struggles with the meaning of their life. Gender at first did not seem to have a relationship with meaning of life struggles, yet when stress was analyzed as a mediator, the total effect of gender on meaning of life struggles was increased to a statistically significant level. These results may suggest males are more likely to endure higher levels of stress which may in turn increase the likelihood of encountering meaning of life struggles than females. This study’s results are consistent with existing literature which reveals relationships between difficult life moments such as depression and anxiety and ultimate meaning struggles (Abu-Raiya et al., 2015).

Limitations & Future Research

A limitation in this study is the age disparity between participants. There were too few participants in the older age range to make appropriate age comparisons.

Future research may be considered in the area of possible mediators or moderators between stress and meaning of life struggles.

References

Abu-Raiya, H., Pargament, K. I., Krause, N., & Ironson, G. (2015). Robust links between Religious/Spiritual struggles, psychological distress, and well-being in a national sample of american adults. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 85(6), 565- 575. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000084

Appel, J. E., Park, C. L., Wortmann, J. H., & van Schie, H. T. (2020). Meaning violations, Religious/Spiritual struggles, and meaning in life in the face of stressful life events. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 30(1), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508619.2019.1611127

Chasson, M., Ben-Yaakov, O., & Taubman – Ben-Ari, O. (2021). Meaning in life among new mothers before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of mothers’ marital satisfaction and perception of the infant. Journal of Happiness Studies, 22(8), 3499-3512. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-021-00378-1

Exline, J. J., Pargament, K. I., Grubbs, J. B., & Yali, A. M. (2014). The religious and spiritual struggles scale: Development and initial validation. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 6(3), 208-222. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036465

Garssen, B., Visser, A., & Pool, G. (2021). Does spirituality or religion positively affect mental health? meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 31(1), 4-20. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508619.2020.1729570

Gutierrez, I.A., Park, C.L., & Wright, B.R.E. (2017). When the divine defaults: Religious struggle mediates the impact of financial stressors on psychological distress. Psychology of religion and Spirituality, 9(4), 387-398. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/rel0000119

Guzewicz, M., Steuden, S., & Szymona-Pałkowska, K. (2014). Changes in the perception of self image and the sense of purpose and meaning in life, among women who lost their child before birth. Health Psychology Report, 2(3), 162-175. https://doi.org/10.5114/hpr.2014.44422

Hayes, A.F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. The Guilford Press.

Lovibond, P.F. & Lovibond, S.H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the Beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behavioral Research Therapy, 33(3), 335-345.

May, M. (2018). Should I stay or should I go? Religious (dis)affiliation and depressive symptomatology. Society and Mental Health, 8(3), 214-230. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156869317748713

Nowicki, G. J., Ślusarska, B., Tucholska, K., Naylor, K., Chrzan-Rodak, A., & Niedorys, B. (2020). The severity of traumatic stress associated with COVID-19 pandemic, perception of support, sense of security, and sense of meaning in life among nurses: Research protocol and preliminary results from poland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), 6491. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186491

Oxhandler, H.K., Pargament, K.I., Pearce, M.J., Vieten, C., & Moffatt, K.M. (2021). The relevance of religion and spirituality to mental health: A national survey of current client’s views. Social Work, 66(3), 254-264. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/swab025

Pargament, K.I. (1997). The psychology of religion and coping: Theory, research, practice. Guildford Publications.

Pargament, K. I., & Exline, J. J. (2022). Working with spiritual struggles in psychotherapy: From research to practice. Guilford Publications.

Raines, A.M., Currier, J., McManus, E.S., Walton, J.L., Uddo, M., & Franklin, C.L. (2017). Spiritual struggles and suicide in veterans seeking PTSD treatment. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 9(6), 746-749. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/tra0000239

Shin, J. Y., & Steger, M. F. (2016). Supportive college environment for meaning searching and meaning in life among american college students. Journal of College Student Development, 57(1), 18-31. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2016.0005

San Roman, L., Mosher, D.K., Hook, J.N., Captari, L.E., Aten, J.D., Davis, E.B., Van Tongeren, D., Davis, D.E., Heinrichsen, H., & Campbell, C.D. (2019). Religious support buffers the indirect negative psychological effects of mass shooting in church-affiliated individuals. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 11(6), 571-577. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/tra0000448

Upenieks, L. (2022). Religious/spiritual struggles and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: Does “talking religion” help or hurt? Review of Religious Research, 64, 249-278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13644-022-00487-0

Wilt, J.A., Pargament, K.I., & Exline, J.J. (2018). The transformative power of the sacred: Social, personality, and religious/spiritual antecedents and consequents of sacred moments during a religious/spiritual struggle. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 11(3), 233-246. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/rel0000176

Wilt, J. A., Exline, J. J., & Pargament, K. I. (2022). Daily measures of religious/spiritual struggles: Relations to depression, anxiety, satisfaction with life, andmeaning. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 14(3), 312-324. https://doi.org/10.1037/rel0000399

Xu, J. (2016). Pargament’s theory of religious coping: Implications for spiritually sensitive social work practice. The British Journal of Social Work, 46(5), 1394-1410. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43905535

Zarzycka, B., & Zietek, P. (2019). Spiritual growth or decline and meaning-making as mediators of anxiety and satisfaction with life during religious struggle. Journal of Religion and Health, 58(4), 1072-1086. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-018-0598-y

Appendix A

SPSS Output

Table A1

Hayes PROCESS

**************************************************************************

Model : 4

Y : RSS_ME

X : Gender

M : DASSSTRS

Sample

Size: 736

**************************************************************************

OUTCOME VARIABLE:

DASSSTRS

Model Summary

R R-sq MSE F df1 df2 p

.124 .015 40.350 11.370 1.000 734.000 .001

Model

coeff se t p LLCI ULCI

constant 28.558 .719 39.723 .000 27.147 29.970

Gender -1.590 .472 -3.372 .001 -2.516 -.664

Standardized coefficients

coeff

Gender -.249

**************************************************************************

OUTCOME VARIABLE:

RSS_ME

Model Summary

R R-sq MSE F df1 df2 p

.462 .213 .614 99.364 2.000 733.000 .000

Model

coeff se t p LLCI ULCI

constant 1.866 .157 11.851 .000 1.557 2.175

Gender -.089 .059 -1.513 .131 -.204 .026

DASSSTRS .062 .005 13.721 .000 .054 .071

Standardized coefficients

coeff

Gender -.101

DASSSTRS .453

Test(s) of X by M interaction:

F df1 df2 p

.240 1.000 732.000 .625

************************** TOTAL EFFECT MODEL ***************************

OUTCOME VARIABLE:

RSS_ME

Model Summary

R R-sq MSE F df1 df2 p

.106 .011 .771 8.325 1.000 734.000 .004

Model

coeff se t p LLCI ULCI

constant 3.651 .099 36.732 .000 3.456 3.846

Gender -.188 .065 -2.885 .004 -.316 -.060

Standardized coefficients

coeff

Gender -.213

************* TOTAL, DIRECT, AND INDIRECT EFFECTS OF X ON Y *************

Total effect of X on Y

Effect se t p LLCI ULCI c_ps

-.188 .065 -2.885 .004 -.316 -.060 -.213

Direct effect of X on Y

Effect se t p LLCI ULCI c’_ps

-.089 .059 -1.513 .131 -.204 .026 -.101

Indirect effect(s) of X on Y:

Effect BootSE BootLLCI BootULCI

DASSSTRS -.099 .031 -.160 -.040

Partially standardized indirect effect(s) of X on Y:

Effect BootSE BootLLCI BootULCI

DASSSTRS -.113 .035 -.181 -.046

********************** ANALYSIS NOTES AND ERRORS ***********************

Level of confidence for all confidence intervals in output:

95.0000

Number of bootstrap samples for percentile bootstrap confidence intervals:

5000

NOTE: Standardized coefficients for dichotomous or multicategorical X are in

partially standardized form.